Dip me in maple syrup and throw me to the lesbians: Exploring the still-smoldering embers of unrealized queer revolutions.

Finding remnant possibilities of queer liberation imagined, hoped for, and built, from the material objects of The ArQuives with Craig Jennex, co-author of Out North.

When thinking about the power of archives, the first place that I think of is Toronto-based The ArQuives, one of the longest running continuous queer archives in North America.

The ArQuives are rich with glimpses into past lives, cultural movements, and the material culture of queerness in Canada and North America.

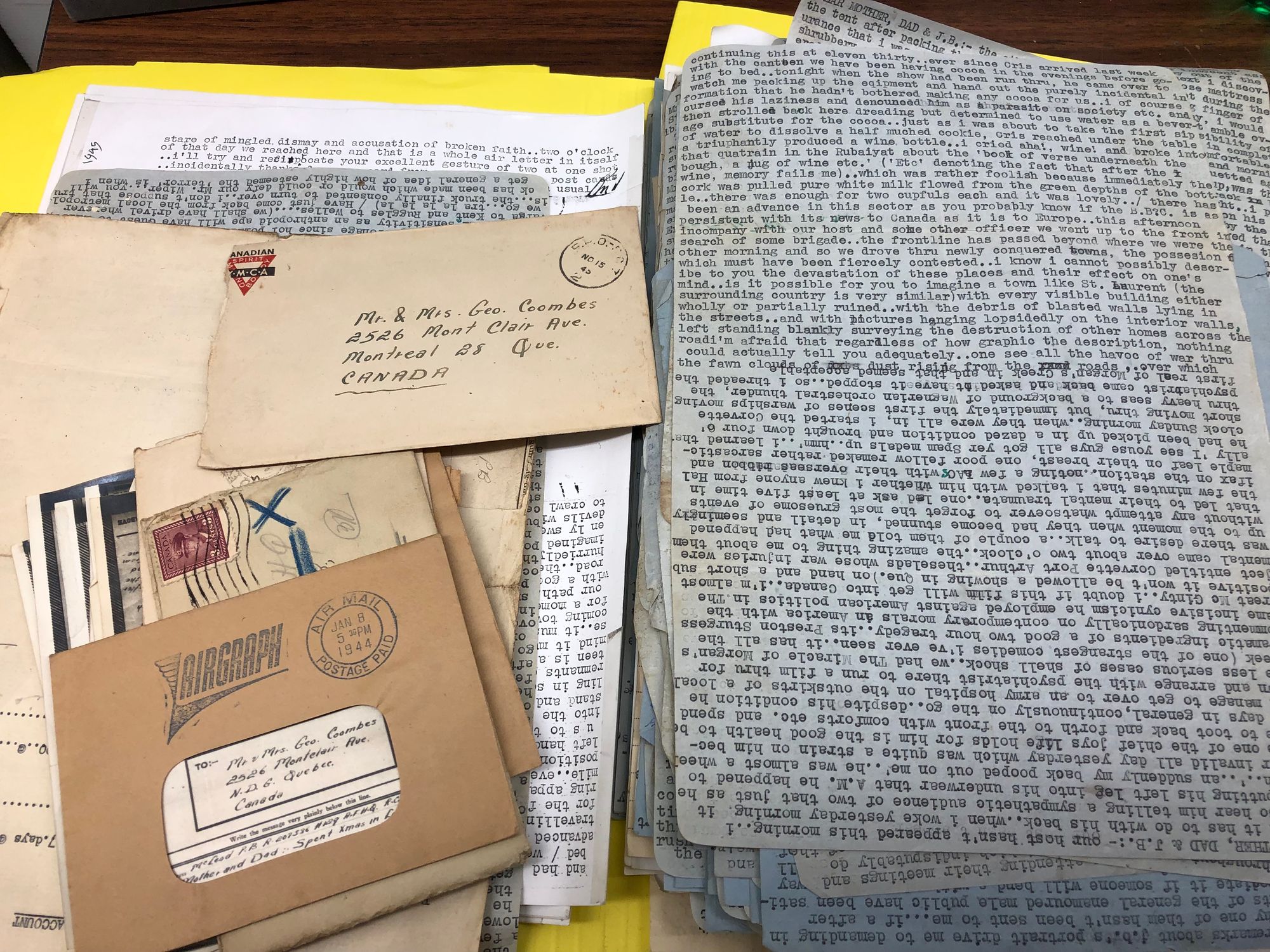

Many of these are gathered in The ArQuives’ book, Out North, which captures the back-and-forth history of queer liberation in Canada through everyday objects and ephemera.

To find out more about the experience of both exploring these archives, and pulling out the threads of history within, I spoke to Dr Craig Jennex, the book's co-author (with Nisha Eswaran), Assistant Professor of English at Toronto Metropolitan University and one of Canada's leading scholars of LGBTQ2+ culture and politics. I started with the easy question — in the face of such a big, complex story, full of revolutions both won and stalled, what's the point of telling it through mundane material culture?

Craig Jennex: What I think is so useful about archives of material culture is that they allow us to remember and return to these moments of political community and collectivity and political progress for queer communities And so these material objects allow us to return back to that history and enliven it in some way that might be useful for the present.

One of the most inspiring things about working on Out North was that Nisha and I just got to spend so much time in The ArQuives with these material objects of the past, and we were just struck constantly by how incredible these were and how useful they were in our current moment .

There's this idea that I see with my students, where we think about archives as these stuffy, boring spaces that are just stuck in the past. But I think what excites me most about The ArQuives is that all of this stuff, all of this material, still has a political force and a function .

And so I think you are correct to see that sort of narrative in the book of this pendulum swing. Because so much of what these material objects offer us is a snapshot of a moment and of how we thought and imagined and built things together. There's just something so beautiful about material objects and material design that allows us to pick up still smoldering embers of unrealized revolutions. There's just something so exciting about these historical materials because they can do something for us. They can completely animate us and enliven us in the present.

"Because so much of what these material objects offer us is a snapshot of a moment and of how we thought and imagined and built things together. There's just something so beautiful about material objects and material design that allows us to pick up still smoldering embers of unrealized revolutions."

Images courtesy The Arquives

You say when you went through all these, you found these incredible pieces. Which ones jump to mind when you say that?

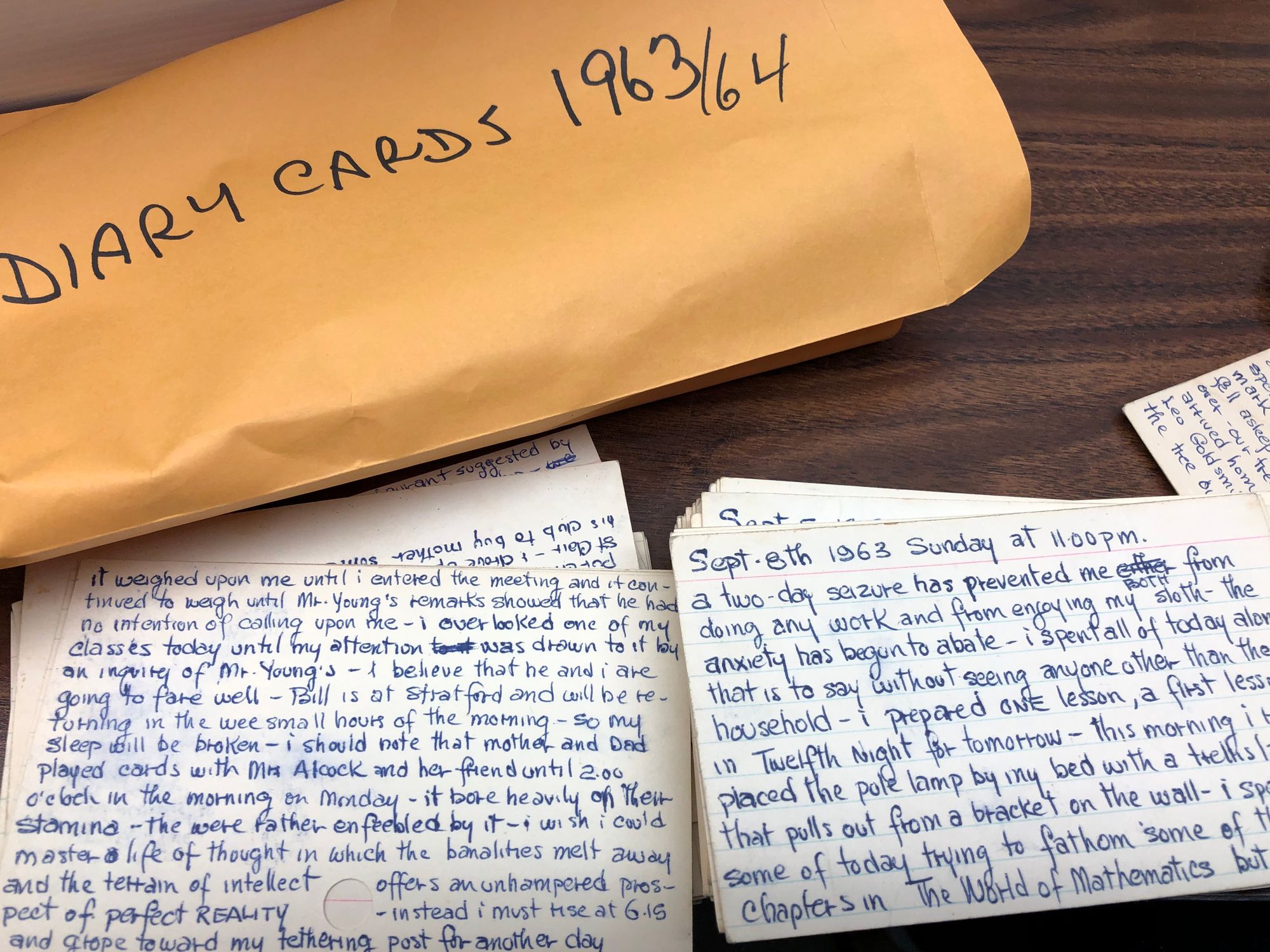

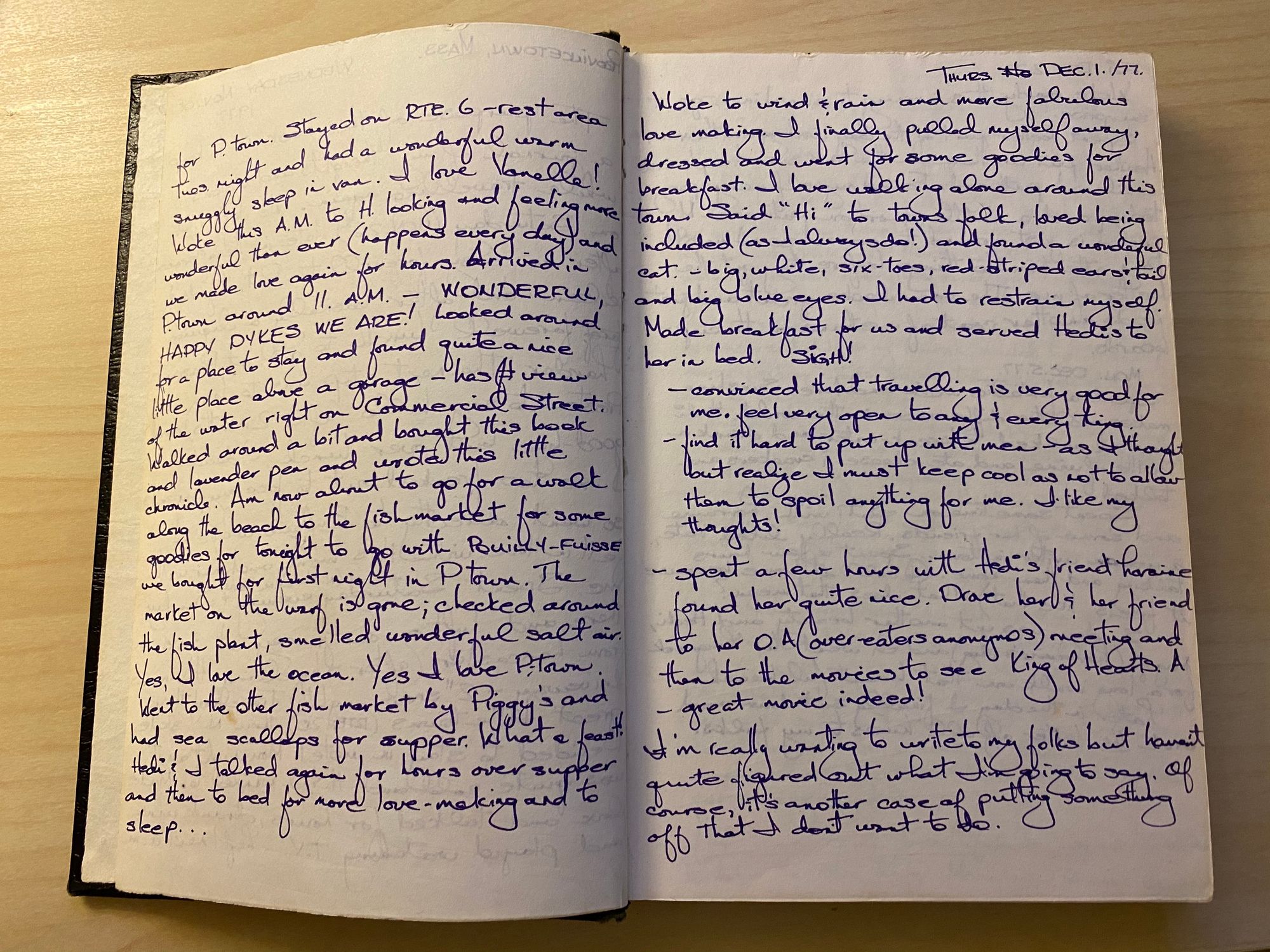

I have some ideas, and it's funny because I bet if we chatted next week and you ask the exact same question, I'd probably say totally different things. But for right now, what is coming to mind is these handwritten diaries and journals that people were writing in the seventies and the eighties, capturing their everyday life.

For me, that stuff is just as exciting as the stuff that is published or put up on billboards or telephone poles around the city, or worn as buttons on someone's jacket. There's something so intimate about these personal diaries and journals, but there's also something ordinary about them, because they're not using them as political manifestos. They're just describing their everyday life and their normal desires and their experiences of falling in love and lust with other people. And so getting to read these personal narratives about what the ordinary queer day-to-day was in previous generations and previous decades is so exciting. They're also handwritten, right? So there's something really beautiful and intimate about reading someone's journal that is written in their own hand with their pen.

Images courtesy The Arquives.

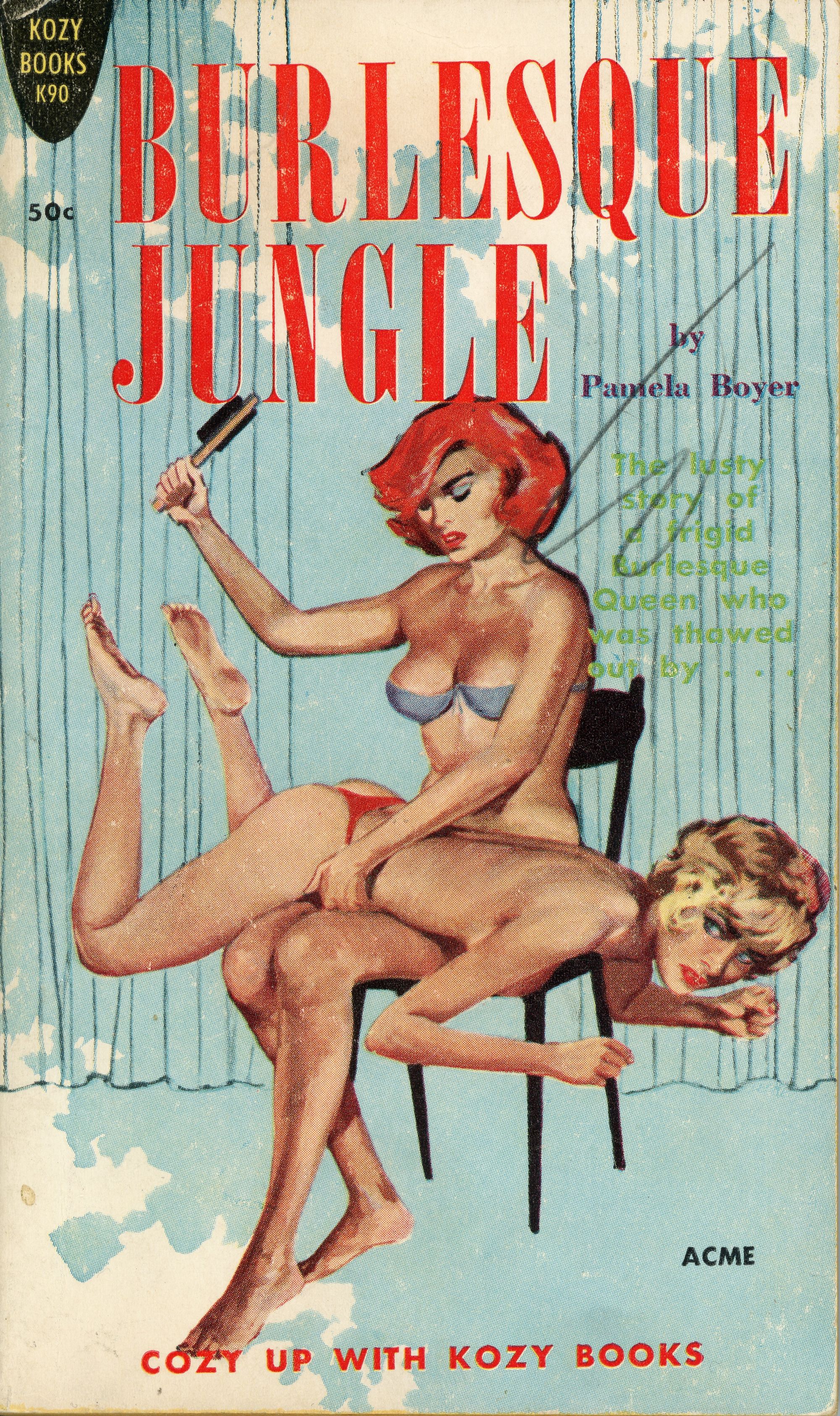

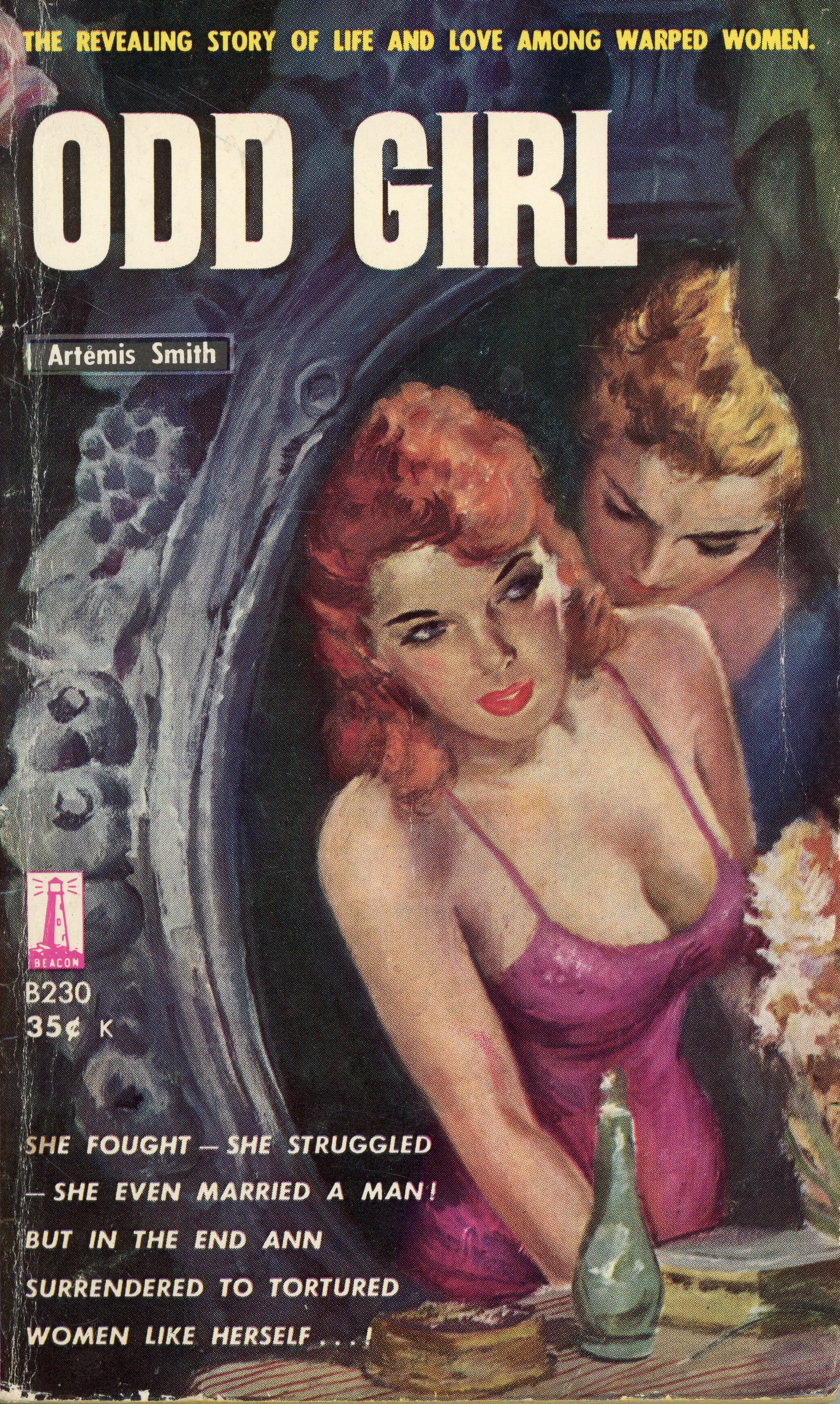

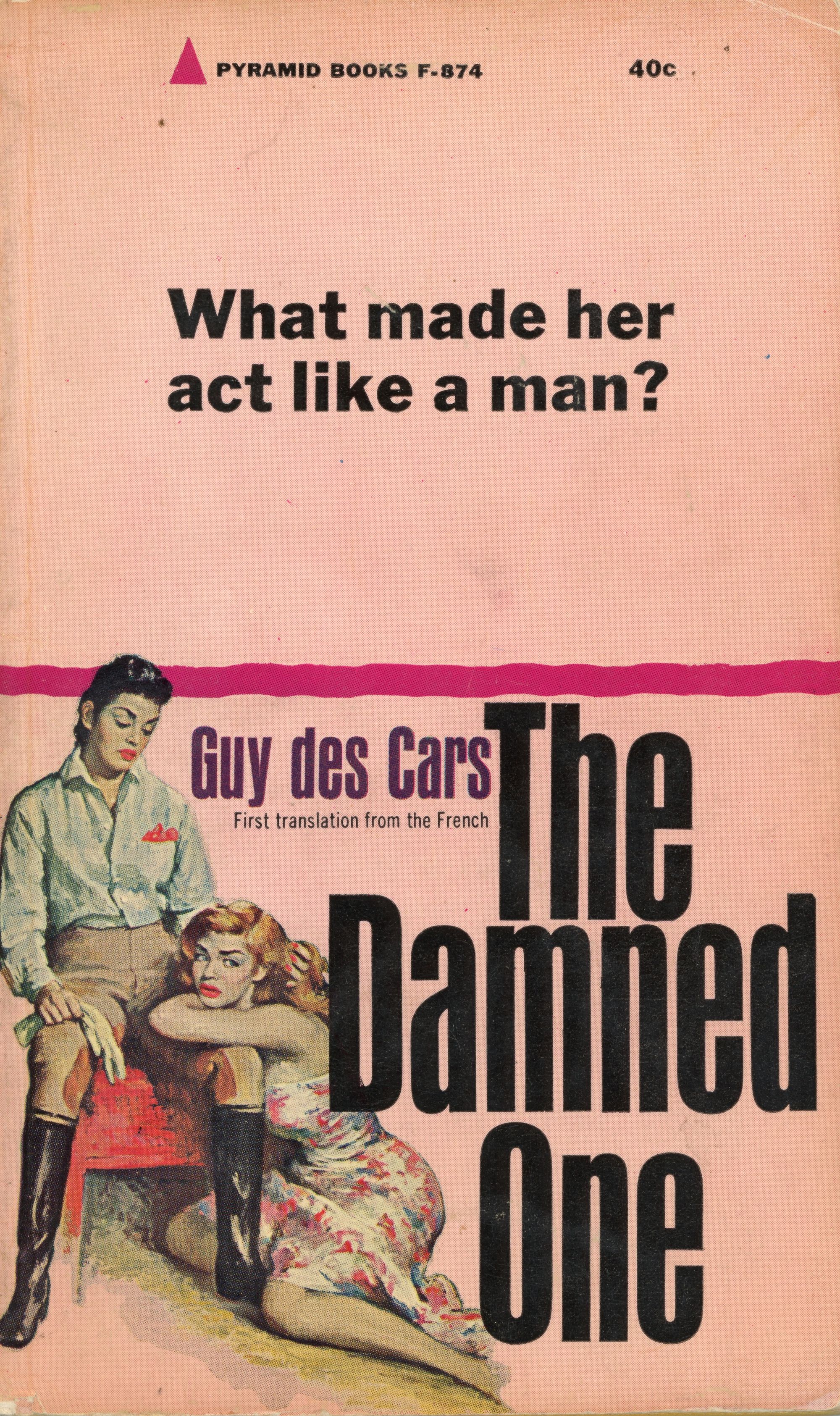

Another is pulp fiction novels of the fifties and sixties, because for a long time those were the only representations of lesbian and gay life that people could access. They're these formulaic, kind of hilarious books that you would basically buy at whatever the equivalent of Shopper's Drug Mart was, and you could read them and hide them in a pocket or throw them out when you're done reading them. But everything about these books is just fascinating, right? Even the cover design, the formulaic way that they present a lesbian tricking a naive young woman into the lifestyle, and then, everything goes wrong and it's just a big catastrophe. There's just something amazing about the fact that for a long time these were the dominant representation in popular culture of lesbian and gay lives, and reading them now, we can't read them, as factual evidence of what lesbian and gay lives were like, because they were so over the top, and voyeuristic and written for straight audiences who just wanted to get a glimpse of this dirty underground world. But they capture something about that moment. And I'm sure for people who think about design, like the cover designs, there's probably things about them that I'm not even picking up on, but I just know that they're so enticing. I just am drawn to them even though they're so problematic.

Images courtesy The Arquives.

I find it interesting that you've picked examples that are both the ordinary, but then almost the superordinary, the extraordinary.

CJ: That's such a good point that I don't think I was picking up on when I was describing that. One is personal representation of the ordinary everyday life. The other is this absurdist representation of an imagined lesbian and gay culture written by people who were not part of that life usually, but were interested in presenting it in a certain way. There's something interesting about that. It's like opposite ends of a spectrum.

It felt like there was almost a connective sense of culture through the objects. Maybe that's looking backwards in the rear view mirror. And maybe through the lens of contemporary culture today, right? Like your drag races these types of things, frames of a sassy, spicy energy.

CJ: It's informed at least by our contemporary perspective, right? And that's one of the things that Nisha and I were desiring and longing for and understanding as connected . But I think this spicy, resistant kind of, “Up yours” attitude is a thread that we can trace back to the early lesbian and gay liberation movement. If we think about it, it's often historicized as starting with Stonewall in 1969, right?

Even though of course there's stuff before that. It's just not a quick and dirty kind of moment of cultural shift in the way that we often present it, but I think there's something worth holding on there because from that moment forward, we see so many examples of this aggressive resistant politicking or collective presentation of self or collective agency.

There's a power in this bitchy, resistant way of thinking about queer life. I guess I'm just thinking about it also in terms of, pre-gay liberation. We have this homophile movement, particularly in the United States in the 1950s that's all about respectability politics. There were pamphlets given out to people who wanted to come and protest. Lesbians had to wear dresses. Gay men had to wear suits. They would walk in a very formal organized line. And so the politics that we see after, the spark of gay liberation is very different and is very aggressive and in your face and resistant and controversial.

Part of why Nisha and I really wanted to pull on that history is because I think that's where we need to get back to in some ways. There needs to be this more in your face, aggressive, resistant queer collective politics.

It's so interesting looking back. Even the choice of homophile as like the title of the movements, “phile” is love, right? So it's like “same love” rather than homosexual, which is “same sex”. They were trying to get away from representations of sex and difference in these things and just say " we're just like everyone else. We wear suits, we wear dresses. We deserve to be assimilated into this culture." And then gay liberation comes along and blows that outta the water and says no, we want something better. We want something more. We want something queerer.

And so tracing the materials allows us to see how these narratives develop and all the different narratives that shoot off of it or contest this or resist this.

You've been in those archives for a long time. Did you find any interesting offshoots?

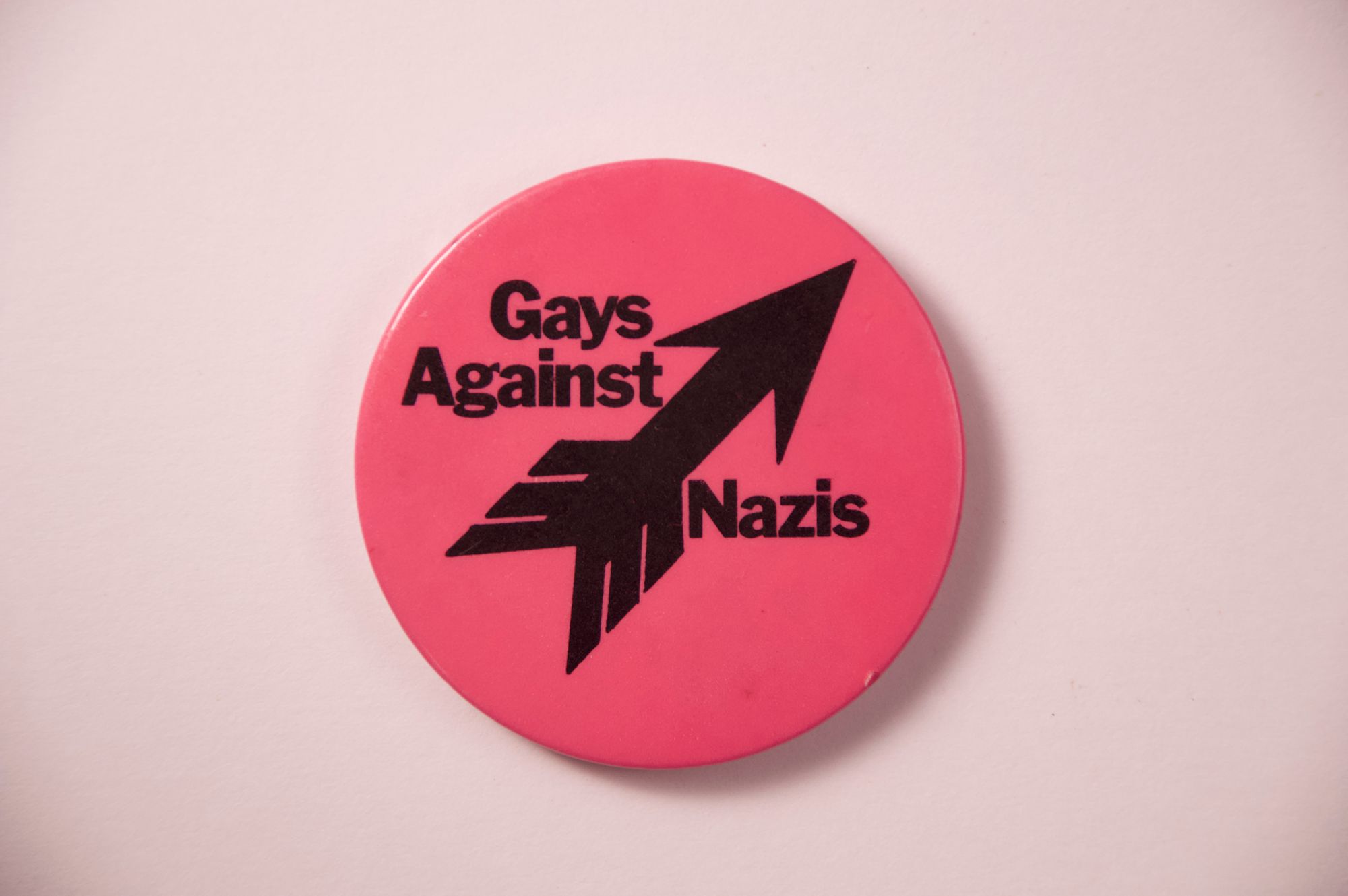

CJ: One of the things that was so formative for Nisha and I when we were looking through this history is that there was this thread of elaboration and coalition politics between lesbian and gay liberation and women's liberation, or black power politics, or anti-racist movements of the decades of the seventies and eighties. Often the way that I think we tend to historize this history is that we think that in the late eighties and in the nineties, that's when notions of intersectionality come in and that's when we start thinking about difference within the movement itself. But what Nisha and I learned was that there was always this thread, there was always this desire for collaborative work between social movements.

Often it was not picked up because the people making decisions were people who were in positions of power and didn't understand the way that black liberation is linked to gay and lesbian liberation. And so there's all these instances where it's not picked up, but that thread has always been there.

One thing we really enjoyed doing was just looking for evidence of that and trying to recognize that this has been a longstanding desire in collective politics.

Thinking about that idea of self-determination, but also the power of The ArQuives, one thing I was drawn to is also how raw and real some of that feels. It's not the politics of being nice or accepted. It's not the sponsorship brochure from TD.

CJ: I'm working on this book now, it's mostly about the 1970s and dance floors. The argument that I'm making is that dance and pleasure on the dance floor is not separate from or secondary to "proper politics". It's actually on the dance floor that people first conceive of liberation and feel, oh, something better is possible.

So I'm trying to flip it to say, dance floors are actually the root of all liberation politics. I've been thinking a lot about the 1970s, and I think there was this shared feeling in that decade, and I'm probably oversimplifying this, but there was this possibility of revolution.

Because there were all these social movements going on at the same time, there seemed to be an actual chance that the world could be radically changed for the better. So it was safer, more just, more equitable, more queer, all of these things. But then the 1980s comes and that gets shut down. For all sorts of reasons. Neoliberalism, the removal of the social safety net, the AIDS crisis, which just decimates lesbian and gay and artistic and black and people of color communities. But in the seventies there was this promise of revolution in the air. There was just this idea that maybe things could be drastically better.

I was born in 1986, so I was not around to enjoy the 1970s, but there's something about this promise of collective liberation that is so exciting to me, and I think that's what has drawn me to The ArQuives because they archive that shared feeling through these materials and through materials we might not even expect.

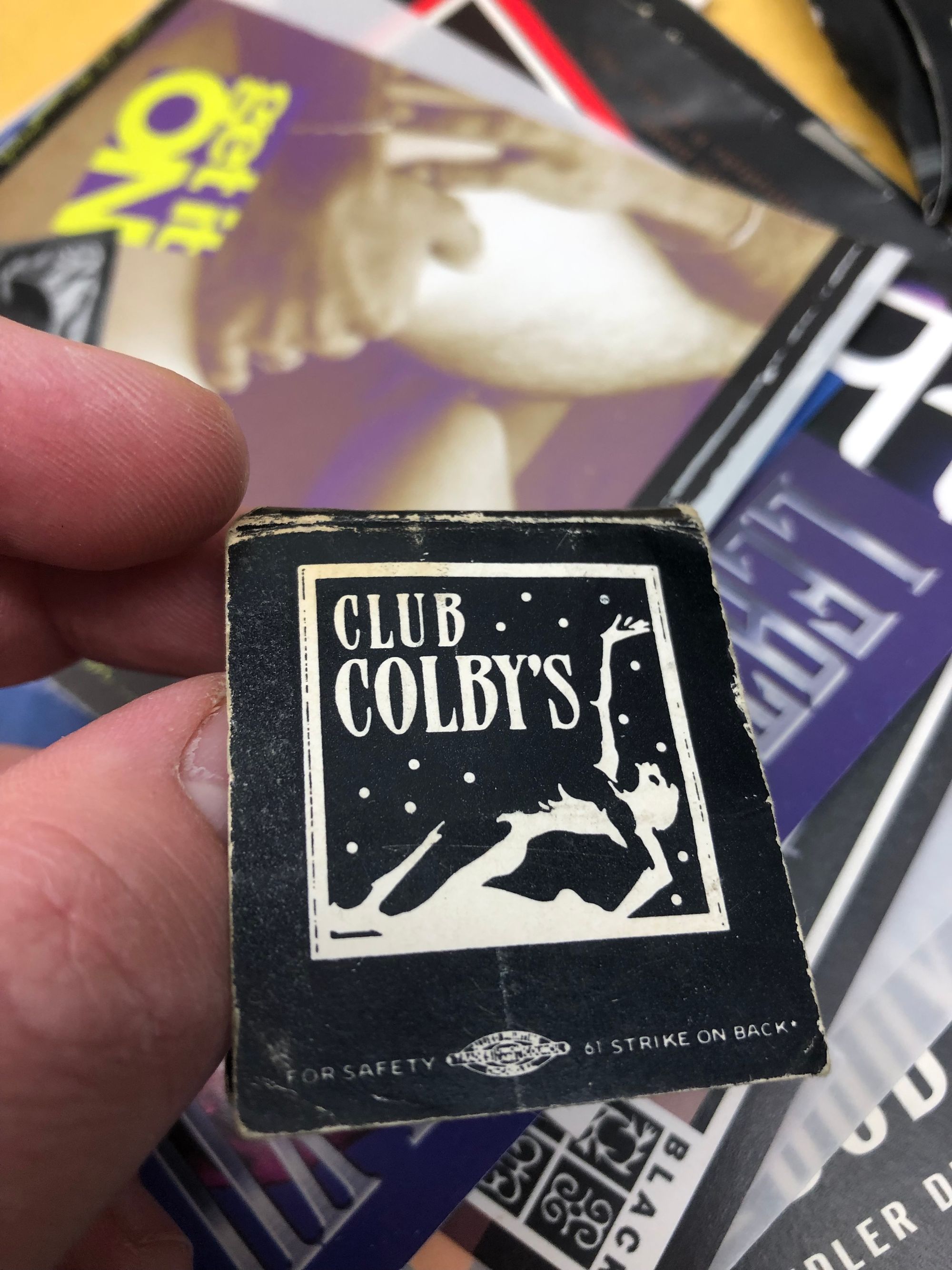

Images courtesy The Arquives.

You mentioned matchbooks as an object that archives this past. I remember when I was digging through the basement of The ArQuives, I opened up one of these matchbooks. It was from the early eighties in Toronto and on the inside of the Matchbook, written in blue pen, was a person's phone number. So I assume it was somebody trying to pick someone up. Here's this little matchbook that was just meant to be thrown out, but now it is archived in this collection. I don't know the specifics of that matchbook or the context from which it comes, but for me it just sparked all of this imaginative possibility.

And that's, I think, the joy of the archive. Finding one object that allows us to think about things that previously seemed unthinkable.

I'm struck so much by that word, imagination. because, it makes me think a little bit of The Queer Art of Failure, right? The author there talks about how childhood is inherently queer — it’s unruly, subversive, unafraid, always failing. A child is full of that imaginative possibility. Would you say it's about imagining?

CJ: So José Muñoz wrote this book, Cruising Utopia. He died in 2013 suddenly, but for the years leading up to that, he was a friend and a mentor. In that book he talks about how hope can and will be disappointed. That's just how hope works. And I think that's how imagination works as well. Hope can and will be disappointed and I don't remember his next line. It's something like, but it must be enjoyed if we're to get through certain impasses.

Basically what he is saying is, yeah, hope will be disappointed. Our dreams, our imaginings of the future, will probably not come to fruition in the way we are imagining in this moment, but the process of imagining, or the act of believing in something, the act of hope, is itself a force. Despite whether we ultimately reach that thing that we are imagining, the fact that we imagine it in the first place is so generative and productive because it changes how we understand the world and our place within it.

To bring it back to archives of material culture, I think what is so useful about so many of these things that are held in The ArQuives is that they have unspecified contours of what they could spark or what they could allow us to imagine. So like that matchbook, for example — who knows the actual context of it? We can read it in certain ways to try to understand what it was and why it matters. But part of what makes it so exciting is that we don't really know, it's not limited to what made it in that moment. The way that I interact with it can just blow everything up, can just spark all sorts of things for me.

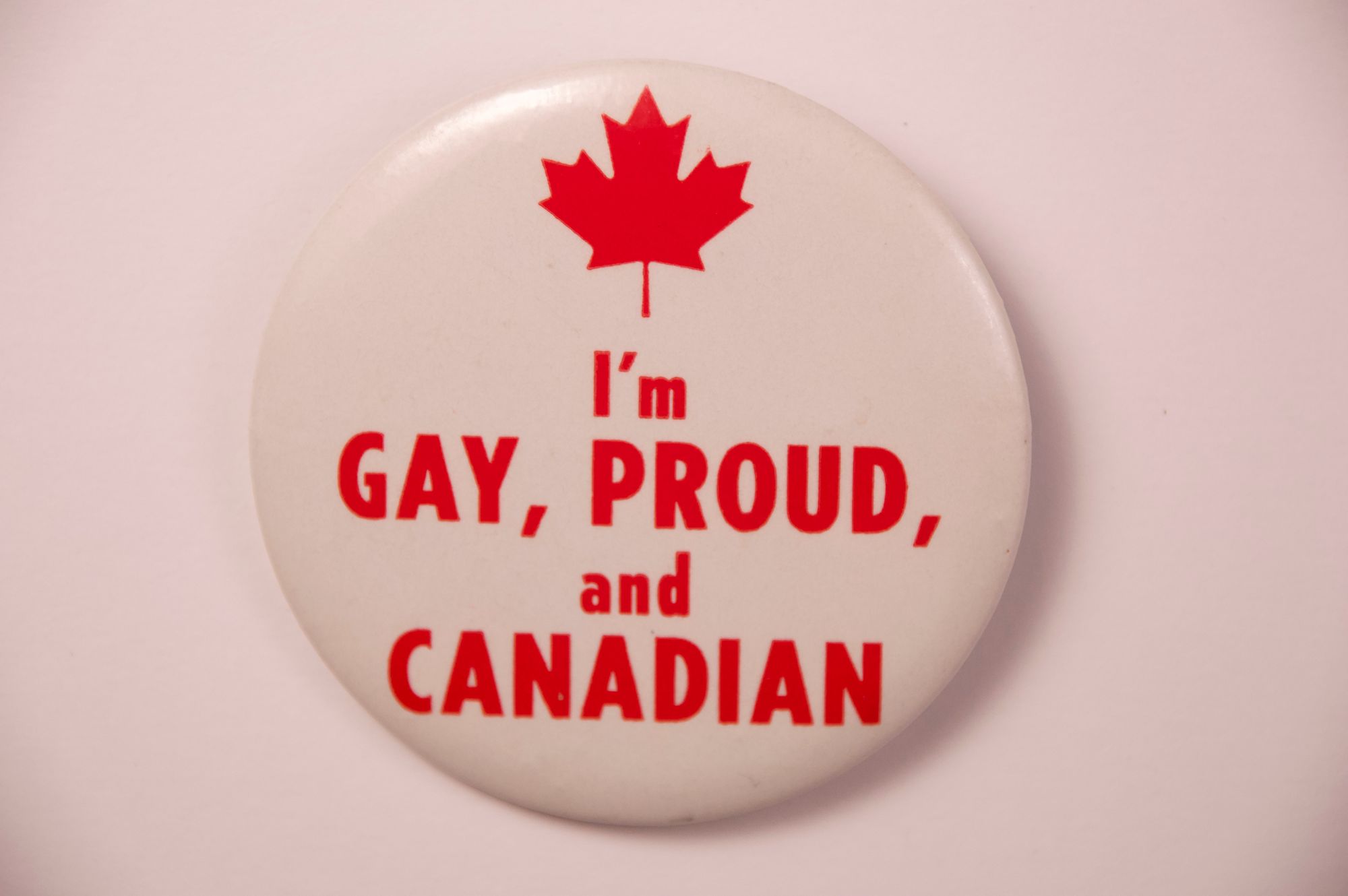

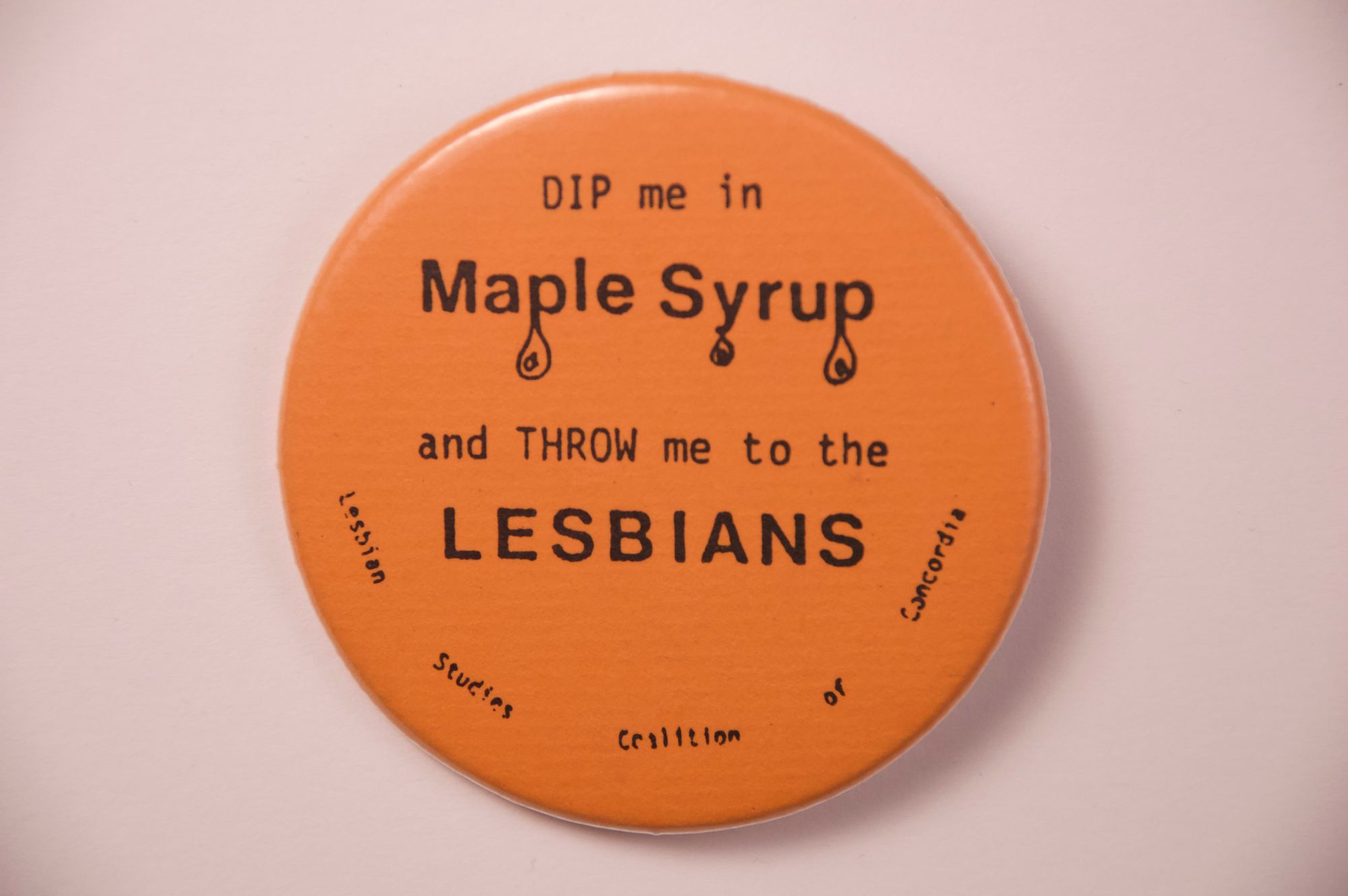

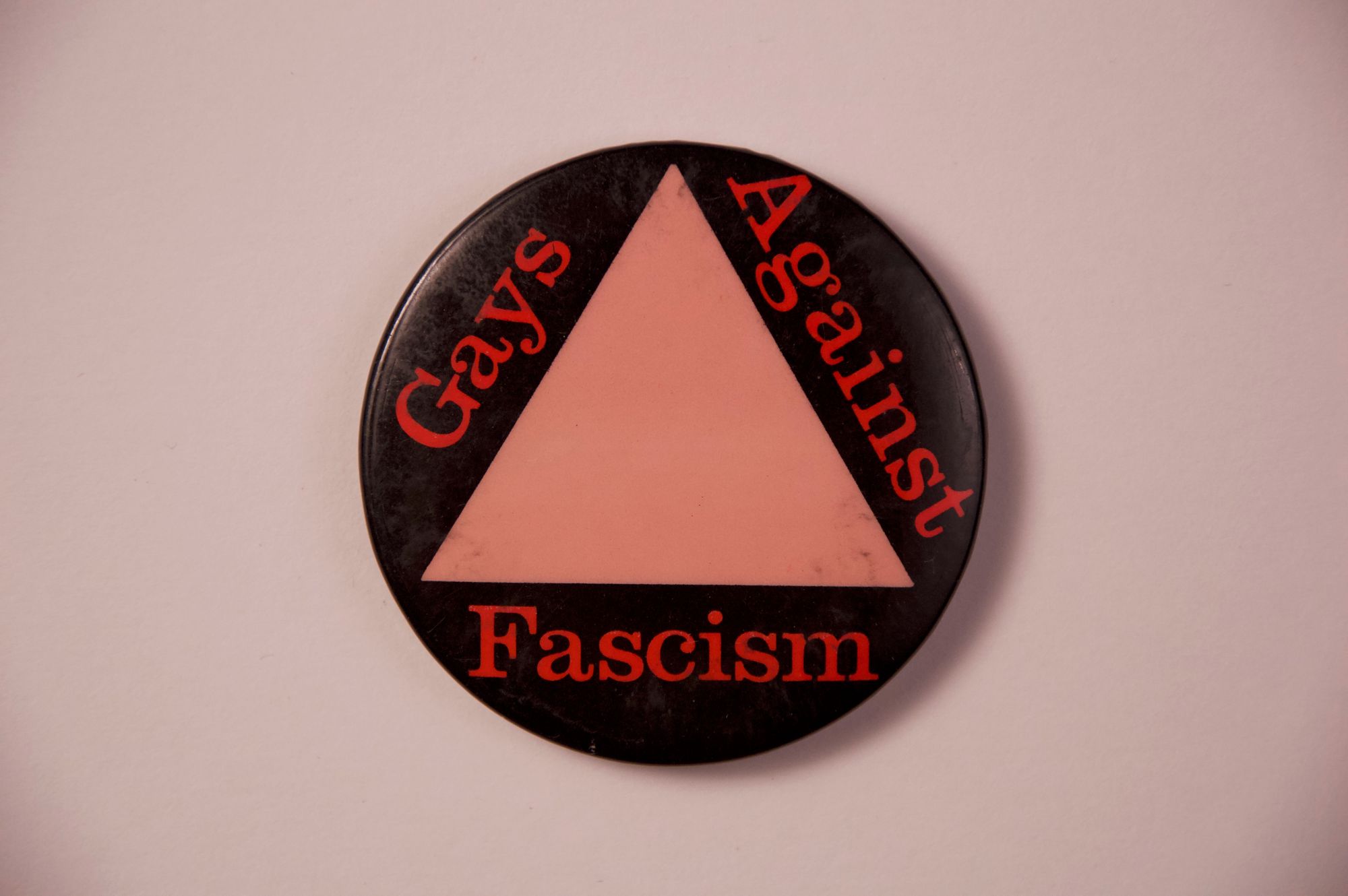

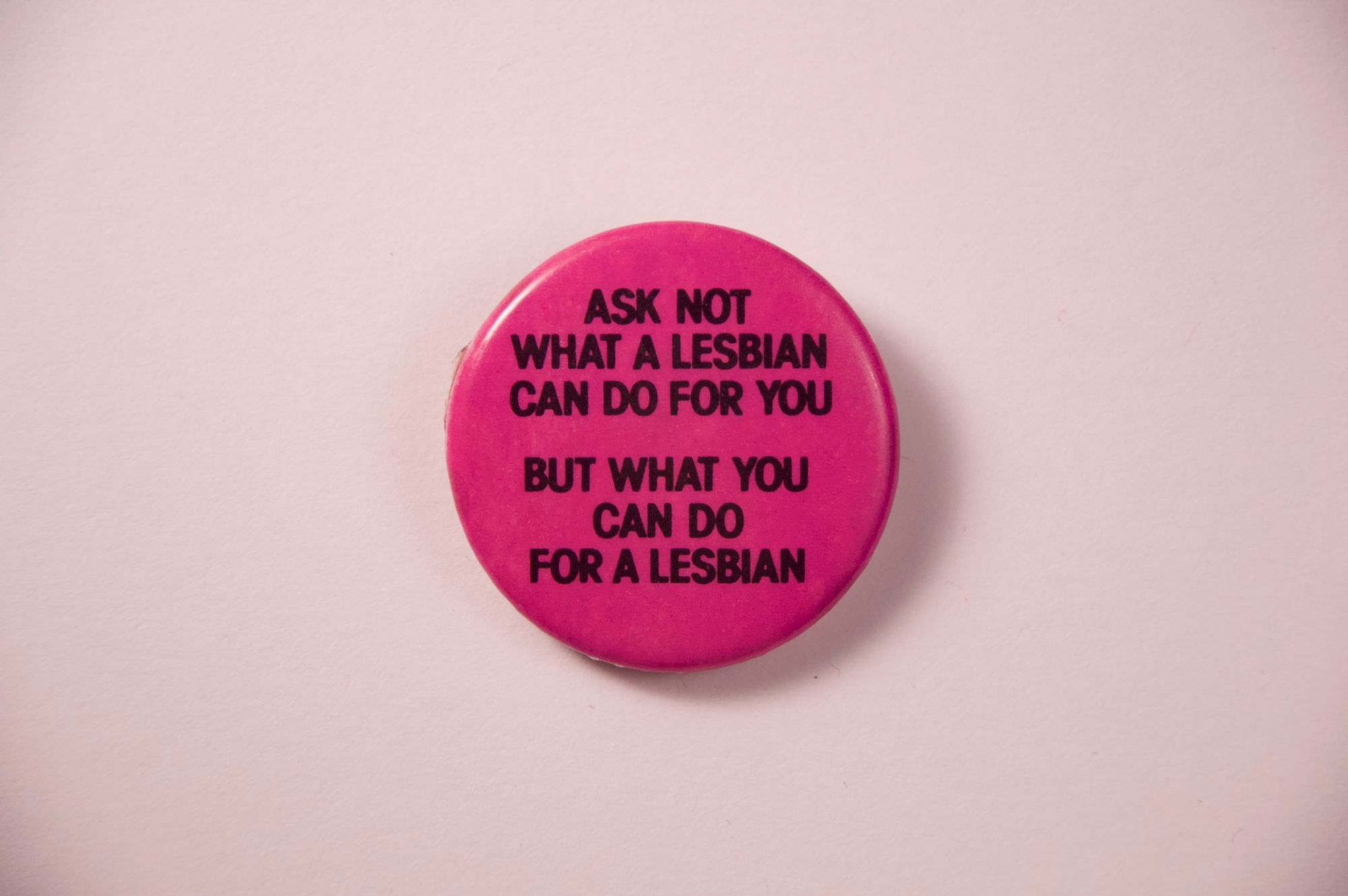

Earlier on, we talked a little bit about humor and messaging. Obviously the pins stood out to me. But I also think that the pins were sparked by so much imperative, especially through the AIDS crisis.

CJ: Pins are incredible. And it's not something that I've thought that much about prior to getting into this history. But now I recognize the profound importance of these very simple buttons.

One thing that I like to think about is, often people would wear pins on their jackets or their backpacks or their shirts or whatever. It's not just a static object, it's something that moves through the city and moves through communities and groups of people as that person moves through it, right? Another thing about pins is that they were relatively inexpensive to create. So if you and I had some sort of brilliant plan for the future or some sort of political statement we wanted to make, we could make that happen pretty easily and we could distribute that throughout the physical space in which we might participate or the people to whom we give pins might participate.

There is something so beautiful about this. Even in moments of profound heartbreak and crisis and death, there are still these moments in which people found joy and bliss and humor together, and the fact that these material objects can capture that and can allow us to see a representation of that is really important.

It's interesting now, many of my closest friends are in their seventies and eighties because of the fact that I volunteer at The ArQuives. But it's so interesting hearing those guys talking about death and dying and aging, because their experience has been so profoundly different than my own. It's just wild to think about. That humor thread exists throughout this history, even in moments when we might not expect it to. Even in moments of profound destruction of the community through the AIDS crisis, there is still this thread that I think can be exciting

Maybe I'm romanticizing it too much, which is something that I sometimes do, but there's something in this history that shows us that we don't always need to take ourselves so seriously. That's not to say that the things that we're dealing with are not serious, but that the way that we deal with them can be multifaceted, can have different approaches and that might allow other people to participate in it differently. It might build up a broader community.

It's not just a static object, it's something that moves through the city and moves through communities and groups of people as that person moves through it.

I've had a few friends who've been on the older queer side who remember some of the bathhouse raids and things like that. And obviously they carried that with them throughout their lives. Now I'm in a different context where I'm mostly in contact with a lot of 25 year olds. That trauma and history of the AIDS epidemic, and the bathhouse raids seem long gone. Queer elders can exist in a way they haven’t in past generations. In a way, this community is in a post-apocalypse state. How do you feel that's impacting the culture of queerness today?

CJ: The way you describe this possibility of connection between generations is, I think, so exciting for me to think about. And it's one of the reasons why I feel really lucky that I've been volunteering at The ArQuives for as long as I have, because I'm not only learning through these materials, but also from the other volunteers and the people who have built up this archive.

I wonder if that's also a promise of this material. And these objects, these things that we have captured because they allow us to feel a connection to previous generations, even those we have lost.

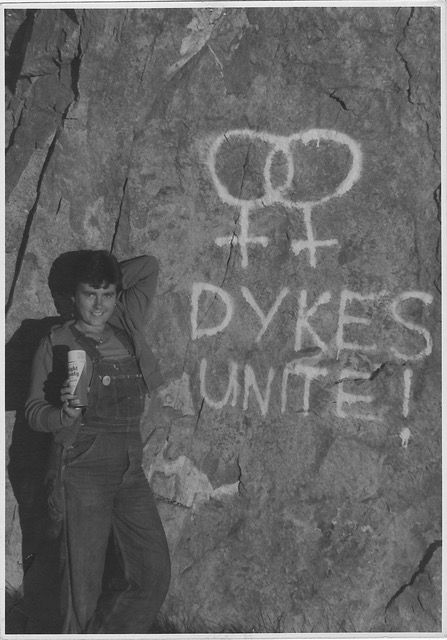

Ang Spalding, and a page from her diary. Courtesy of The Arquives.

When we started chatting, and I mentioned that one of the things that I found most exciting was these personal diaries. I was thinking about one in particular. It was written by this woman named Ang Spalding. She traveled the continent with , with a few other lesbians. They called themselves the Van Dykes because they were lesbians driving around in a van. It was just incredible. When I was reading her diary about this trip, it felt like I was learning from her. I was gaining all of this knowledge from this queer elder who has been dead for a long time now.

But this material object allowed me to continue to connect with her long after she passed. And because these material objects are personal and so intimate, that connection feels really important to me.